The Alewife-as-Witch Myth Revisited

No, medieval alewives are not the archetype for the modern pop culture witch

It’s the most wonderful time of the year. Spooky season is in full swing, the scents of fresh apple cider and falling leaves fill the air. Halloween decorations adorn houses gathering delighted gasps of passing children. Pumpkins decorate the storefronts and we gather in hushed tones to exchange tales about all those things that go bump in the night. It is, after all, the best time for ghost stories. Halloween is my favourite holiday and this year is no exception. But like every year in the past decade, the sights and scents of autumn are also met with something else: The approximately 10,000 articles, podcasts, and videos telling you that in the medieval period alewives were en masse accused of witchcraft; because women who brewed were thought to be magickal. Thus these medieval women were all pushed out of brewing and that’s where we get the modern witch stereotype.

At first, it sounds like a likely story, something that feels like it should be based in reality. After all, there are credible links in art between alewives and demons. Even the devil himself.

However, the reality for medieval, and even later, brewing women wasn’t one lived in fear of witchcraft accusations, at least not because they made ale. They had many things to worry about, famine, war, the Black Death. But concerns that simply because they brewed ale they would be thrown to the mercy of the courts for witchery was not of consequence.

I am going to take you through this myth, breaking down all the parts and pieces to reveal the true story of brewing women. Starting with some much needed context, some background if you will, of brewing, and witch trials, in the years 1200-1700 in England, Scotland, and Wales.

***

I’d like to begin with a timeline.

The medieval period is generally defined by scholars as the years between 500-1500.

As many scholars like Judith Bennett have established, brewing in England was dominated by women during much of the medieval period. The same can be said of Scotland and Wales. To be clear, men certainly brewed, often alongside their wives as part of a couple. As time wore on, men would come to dominate the industry in many contexts, but not all. And this would differ greatly depending on precisely where and when the brewing took place. There was, however, never a time when women weren’t involved in the brewing trade. I covered this in my recent book The Devil’s In the Draught Lines: 1000 Years of Women in Britain’s Beer History published with CAMRA.

So we can see that women were definitely brewing in the medieval period.

Fast forward in time to the early modern period which is defined as those years between 1500-1800.

Now, the witch hunts, for the most part, didn’t take place in the medieval period. That’s not to say there wasn’t a few here and there, but what we envision when we think of them was largely an early modern phenomenon, with most happening in the late 16th and 17th centuries.

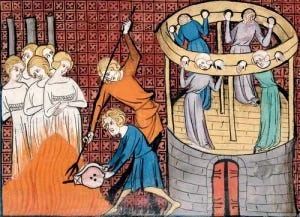

So right off the bat, we can dismiss the idea that medieval alewives were charged with witchcraft, because it wasn’t medieval women at all. Whilst, yes, there were some people accused of practicing maleficium or evil magick, medieval people were primarily concerned with heretics and not witches.

We can outright eliminate the idea that medieval alewives were removed from the trade via witchcraft accusations. Indeed, women kept brewing right through the medieval period. Though there were a few things that would impact the brewing world, leading to an increase in male brewers, these were not related to witchcraft.

But what about their early modern counterparts?

In The Devil’s In the Draught Lines, I took a look at books written for and by women in between the years 1500-1900. Within the pages of recipes or instructions on how to run a household, were beer recipes. Brewing techniques and the importance of malting graced the pages of these works, not just for the household, but also for sale to their neighbours. In fact, many of these published books of the time held brewing as a key part of being a housewife.

Whilst those witch trials were going on, people were declaring that brewing was an essential skill for women. We can see then, that brewing was not viewed as something evil when women did it, not at all. It wasn’t inherently associated with witchcraft. I conducted a study of the witch trials in England, Scotland, and Wales and found that the trials themselves showed no credible links between women brewing and being accused of witchcraft because they brewed. In fact, women who brewed were on both sides of the trials, as those accused and accusers. Women who brewed had their ales cursed by supposed witches or weren’t able to brew at all. Brewing was ubiquitous and so it appears in the trials alongside other such food stuffs, like bread, eggs or milk. I published all the details of this research in The Devil’s In the Draught Lines for more specifics.

So women were not pushed out of brewing because they were accused of witchcraft. Not in the medieval period, and not in the early modern. Women would continue to brew well into our modern era, though certainly not in the same numbers they had done so in previous centuries.

***

Now, on to the pop culture witch stereotype and where it really comes from.

I dispelled the myth that this stereotype comes from alewives in 2017 on my blog, Braciatrix, and all the points I made there still stand, though I will briefly summarise them now.

Essentially, the introduction of the pointy-hat clad witch comes from children’s chapbooks dating to the late 17th or early 18th centuries. See for example, The History of Witches and Wizards: Giving a True Account of All Their Tryals in England, Scotland, Sweedland, France, and New England … Collected … By W. P from the 18th century. You can get the free ebook from Google to have a look yourself to see this sort of illustration.

Of course, like I said, this wasn’t the only way witches were depicted in the 18th century. Goya famously painted them with pointed hat without the brim.

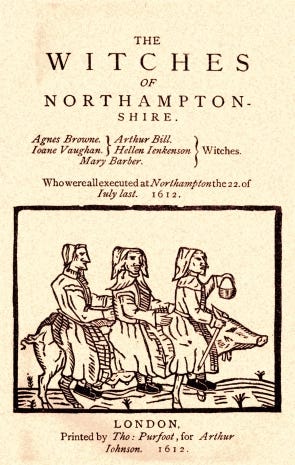

During the witch trials, witches themselves were depicted as normal people, wearing the garb of their neighbours. Normal clothes. This hinted at the insidiousness of their evil magick and perhaps made them so terrifying.

So where did the pointy hat clad witch come from? I think the two most plausible connections come from Peter Burke’s assertions that the witch hat, and indeed the portrayal of the witch with a hooked nose, stem from virulent anti-Semitism.

The other is that it came from the capotain hat from the late 16th and 17th centuries, often depicted in paintings of men and women. As I said in my article, ‘This hat was associated with Puritan costume in the years leading up to the English Civil war and the age of the commonwealth. Usually hats in these portraits had flat, rather than pointed tops. But some certainly were pointed like this pièce de résistance currently in collection at the Tate.’

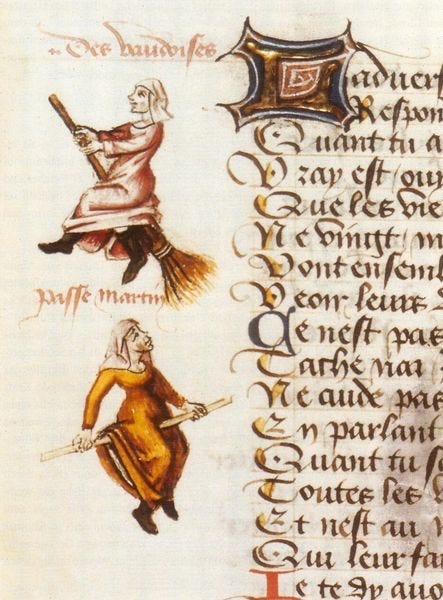

Brooms, and the concept of flight, are another matter entirely, precisely because in a lot of trials flight wasn’t even a factor. When it was, so-called witches were portrayed as riding sticks, shovels, pitchforks, animals, or even the wind itself. Why was the broom so common? Scholar Brian Levack argued that it was simply something many women would use and since many of the accused were women, it stuck.

As for the cats, well, they were associated with heretics long before witches. And so, during the shift of accusing heretics to witches, cats came along for the ride. The Templars famously were accused of worshipping a cat during their trials for heresy, and they weren’t the only ones.

Historian Kathleen Walker-Meikle contended that cats were associated with heresy and later witchcraft, because of their liminal status, representing both domestic and wild. To be certain as well, women who were accused of witchcraft kept a variety of familiars besides cats, like dogs, toads, bats, and often ferrets.

**

To sum up, medieval English alewives were not pushed out of brewing due to witchcraft accusations, nor were their Scottish and Welsh counterparts. Later, in the early modern period, during the witch hunts, women would continue to brew, and like the earlier women, would not be accused of witchcraft simply because they did so. Brewing women were not viewed as inherently evil or caught up in evil magick. Nor were they believed to be witches simply because they took part in this trade. There is a lot more to this than I could ever dream to cover in a post here, and if you want more of these details I would highly encourage you to read my book, The Devil’s In The Draught Lines, where I have devoted a lot of work to this topic.

Suffice to say, that the modern pop culture witch stereotype, doesn’t come from these brewing women, but has its links elsewhere as we have seen.

As I stated previously, I totally understand why this myth is so pervasive. It feels like it could be true based on the art and literature that shows alewives in hell or cavorting with demons, but when we dig deep into the historical sources we can see it quickly falls apart.

Alewives were not en masse removed from brewing because of witchcraft accusations. Medieval and early modern people did not view brewing women as inherently witchy; and the modern pop culture witch stereotype does not come from alewives.

Thanks for reading!

The Devil’s In The Draught Lines: 1000 Years of Women in Britain’s Beer History is available online and in all good bookshops in EU/UK. Available online as an ebook on Amazon in US.

**

Sources and Further Reading

Judith Bennett, Ale, Beer and Brewsters in England: Women’s work in a changing world 1300–1600, (New York, 1996)

Theresa A. Vaughan, ‘The Alewife: Changing images and bad brews’ in AVISTA Forum Journal Vol. 21 Number ½ (2012)

Ralph Hanna, ‘Brewing Trouble: On Literature and History- and alewives’ in Barbara Hanawalt and David Wallace (eds.) Bodies and Disciplines: Intersections of Literature and History in the 15th Century, (Minneapolis, 1996), pp. 1-18.

Michelle M. Sauer, Gender in Medieval Culture, (London, 2015)

Miriam Gill, ‘Female Piety and Impiety: Selected Images of Women and Their Reception in Wall Paintings in ENgland After 1300′ in Samantha J.E. Riches and Sarah Salih (eds.) Gender and Holiness: Men, Women, and Saints in Late Medieval Europe (London, 2002), pp. 101-120.

Miriam Gill, Late Medieval Wall Painting in England: Content and Context (c.1300-1530) (PhD Thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 2002)

Barbara, Hanawalt, “Of Good and Ill Repute”: Gender and social control in medieval England (New York, 1998)

Peter Burke, Eyewitnessing: The Use of Images as Historical Evidence, (Cornell, 2000)

Catherine Rider, Magic and Religion in Medieval England, (London, 2013)

Brian Levack, The Witch-hunt in Early Modern Europe, (Harlow, 2006)

Peter Burke, Eyewitnessing: The Use of Images as Historical Evidence, (Cornell, 2000)

Charlotte-Rose Miller, Witchcraft, the Devil, and Emotions in Early Modern England, (London, 2017)

Kathleen Walker-Meikle, Medieval Pets, (Woodbridge, 2012)

Catherine Rider, Magic and Religion in Medieval England, (London, 2013)

Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger, Malleus Maleficarum, (trans. and intro.) Montague Summers, (New York, 1984)